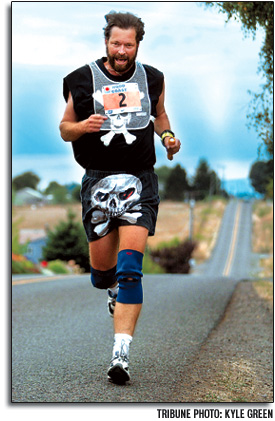

Twilight finds team captain Randy Gibbs, who founded Kult Kevorkian in 1994, loping along near Boring at a respectable pace: 8 minutes, 15 seconds per mile. A 346,720-yard dash Running Oregon's beloved Hood to Coast relay is all about the puns and the fun

By JOSEPH GALLIVAN

Issue date: Tue, Aug 26, 2003

The Tribune

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It's 11:15 a.m. Friday when Mike Ball loads a panel van with backpacks and food in preparation for team Kult Kevorkian's trip to the starting line of the Hood to Coast relay race. Other team members pull up outside his home in Northeast Portland. "This is my brother John," says Mike, 44, pointing to a fit-looking 52-year-old with silver hair. John Ball tapes Kult Kevorkian signs to the side of the van and writes the word "Kaution" in blue tape on its rear. "When my brother Dave ran on this team, we were going to have as our team motto 'We've Got Balls,' but we decided against it," he says. It soon becomes clear that a Hood to Coast team without a silly name looks naive or, worse, boring. The ruder the pun, the better the reaction. As the six-person van heads through Gresham toward the starting point on Mount Hood, team vans decorated with words and objects pass by: "Thugs and Jugs," "Sporting Wood." Others teams stick to running gags: "It's Good to Coast," "Dead on Arrival," "Blister Sisters" and "Not Leaving 'Til We're Heaving." When runners from other teams appear heading west on 26, the team puts on its game face. "Nice form," says Mike from the driving seat as a seemingly weightless girl springs by. Next comes a heavyset man, waddling, chafing, sweating. "Ooh," say several people at once, feeling his self-inflicted pain. "You get more out of shape men doing Hood to Coast than women," explains Mike. "Because they're in denial." In Sandy, a tan automaton in a jog bra passes, six-pack rippling, ponytail swinging. "Goodness," says Mike, and the van falls silent. 1:15 p.m. Timberline Lodge, Mount Hood Hundreds of runners mill around waiting for their start time as the occasional baffled snowboarder picks his way through parking lot. Out-of-towners pose for photos on a rocky stump in front of denuded Mount Hood. It's ugly, and brown, and awesome. Van drivers, who must work through the night, pick up their "free energy pack": six cans of Red Bull. The members of the Wild Ekin Team, a collection of tall lads in spandex, talk excitedly in broken English. They are Nike sales reps. "We're called 'Ekin,' 'cause we have to know the product backwards," says one, a young man from Sunderland, England. They're easily visible in gray "H2C" sweat shirts that will turn up everywhere for the next 36 hours, as they are one of 20 or so Nike teams in the race this year, all immaculately dressed and on message. The Hood to Coast starting-line announcer, John Hammarley, has flown in from Dallas for his 17th year of getting teams prepped and pumped for the send-off. He starts a bunch of teams every 15 minutes, from 9:30 a.m. to 8:45 p.m. He loves it. The group hugging already has begun. Hammarley just starts the whooping. 1:45 p.m. Timberline Lodge Leah Henriksen gets Kult Kevorkian on the road, descending 2,000 feet in six miles. Henriksen's father is John Ball. She has gotten her husband of one month, Matt, on the team. Since she was 4 years old, her father has encouraged her to run. He has warned her not to go down the mountain pell-mell, or she'll pay for it later in her quads. She also must stretch her iliotibial band, a strip of thigh tissue that runners get excited about. John knows a lot of stuff. Jared Billings, who runs Kult Kevorkian's second leg, perks up at the talk of muscles. He's a mechanic and a bodybuilder, 260 pounds. He eats 4 pounds of chicken a day. The others worry about his running since he used to be skin and bones. But he did produce this fine van, with room for three to stretch out in back. Hood to Coast has blossomed since its eight-team origin in 1982. But one of the things that makes it peculiarly Oregonian is the fact that its size has been capped. In 1999, the number of teams of 12 allowed was limited to 1,000, for the sake of logistics (congestion, litter, paperwork). That limit remains. The roster fills completely every October on the first day that registration opens for the next August's event. Each team travels in two squads of six, alternating after each runner in one van has run a leg. Space-hogging RVs and campers are not allowed, only small vans. Most runners rough it in minivans with the back seats removed. If there's time for sleeping, it's done in a bag in the open air. The van in front of the Kult most of the way this year sports the international symbol for not being a spoiled brat: a red circle with a bar across the word "WHINING." 2:30 p.m. Government Camp That doesn't mean to say runners can't indulge in their favorite pastime: talking about their bodies. "I sped up at the end and felt like throwing up," Leah says cheerfully. She comes in in two minutes faster than her estimated time. Everyone congratulates her and the next runner, her husband. Everyone's talking about the Barefoot Dude. Web developer Chris Runyan, 36, is running the race for another team barefoot and shirtless. His soles resemble the asphalt they pound. His armpits are white with foaming sweat. He decided to go shoeless two years ago. He ran the Portland Marathon this way last year. "When I worked at Inspiration Software, they used to encourage me to go barefoot," he says, "but when I moved to my current job in Bellingham, Washington, they made me wear shoes." He shows a powdery yellow toenail as evidence of the unnatural evils of footwear. "Fungus." He could go on, but his teammates pull him away. They have to hurry ahead to the next exchange. 6:40 p.m. Sandy The first six legs are completed, and Van 1 hands off to Van 2 in the parking lot of the Thriftway in Sandy. This year, team captain Randy Gibbs, who founded Kult Kevorkian in 1994, has agreed to forgo the limelight and take Van 2. Normally, he runs full-tilt through the mountains waving his skull and crossbones flag. "Most teams go to a pub and discuss who is going to run which leg," Gibbs says, his clip-on pirate earring glinting in the sun. "Inevitably, they get all upset and piss and moan. So I just assign the legs and let them take their lumps." Everyone on the team accepts Randy's benign dictatorship because he's the institutional memory and the inspiration. He's greeted by old race pals at every stop. Even his wife, Kathy, also a runner, smiles at his antics. He razzes girls and winds up strangers with his assisted-suicide jokes. The team logo mutates every year; sometimes it's a Grateful Dead theme, sometimes a modified Old Glory. 7:52 p.m. Boring In electric blue twilight, Randy Gibbs pounds down the road through the Christmas tree farms of Boring. He's averaging 8 minutes, 15 seconds per mile. Respectable for a man of 48. Talk constantly revolves around performance, minutes per mile. "So-and-so is running sixes" is usually accompanied by "Wow!" Tens are like, so blah. Today, running is seen as a way of pushing yourself, and thus a way of feeling your age. The results come back differently every year, and after a certain point they only get worse. "You know, some of these guys in their late 20s, they're not what they used to be," he says later. "They can't just train for three weeks and do it." At Gresham, runner Patty Payne is worried about the Springwater Corridor. "It's pitch-black out there, and you can be all alone. One year I got alongside this guy for safety, but when he found out I was married with two kids, he took off," she says, laughing. Police patrol the pathway on two wheels, but many of the women joke nervously about the supposed "bums under the bridge." During the night, a rumor circulates about a woman runner being dragged into the bushes in Northwest Portland but managing to fight off her attacker. According to the organizers, nothing was reported to police. Randy has a theory about men and women runners. "Men tend to run in spurts; women run slow and steady. So if you fall in behind something cute and cuddly, you can daydream for a while." 10:55 p.m. Southwest Bancroft Street and Moody Avenue, Portland Van 1 takes up the race again, heading through downtown off to Northwest Portland. At the official exchange just off Southwest Macadam Avenue, a huge crowd is gathered under arc lights. This is runner's world: Spaghetti Factory pasta dinners for carbo-loading, funny little gels for calories on the go, all sorts of flashlights for sale. In the backs of minivans, you see flats of water and PowerBars. Runners are all about being organized: two pairs of sneakers, four pairs of socks. Van 2 heads back to Randy's house in Tigard for food, showers and the hot tub. It's a nice house: two cars out front, basketball hoop, U.S. flag. His garage is taken up with an enormous train set that he lets his two kids play with. "This is my 'I Love Me Wall,' " he says, pointing at dozens of framed photos. Many are from previous runs. He started running in his late 30s as a distraction while trying to quit smoking. A large chrome hoop holds a sheaf of numbers from all sorts of races. The pictures go all the way back, showing a young man growing up in the early 1970s. He gets out his box of H2C scrapbooks. 1:10 a.m. Saturday Tigard Randy and Van 2 head north on Highway 30 for the Columbia County Fairgrounds. His race tape is all warped, so he settles for Jimmy Buffet instead, then oldies radio. He and his wife sing along to "Itchycoo Park" by the Small Faces. But the Rolling Stones are his favorite, and he likes to blast Hendrix when he's home alone. As the van passes other contestants, the runners' reflective strips dance like fireflies in the dark. At the fairgrounds, people sleep despite the constant slamming of Honey Bucket portable toilet doors and the revving of engines. Out on gravel roads of the Coast Range, though, a crescent moon hangs low, accompanied by Mars. The world's troubles seem far away. 6:37 a.m. Exchange 24, in a field near Mist The temperature is in the 30s. Runners fresh from finishing sweat next to others swathed in fleece. People stand in line while the Honey Buckets are slurped clean by a vacuum pipe on a tanker truck. The girls from the local equestrian club have set up a stand selling coffee, pastries, pancakes. This army marches on its washboard stomach. Levi Whiteman of the Mist Birkenfeld Fire Department mans the first aid gazebo. He estimates he has treated 3,000 runners so far, mostly for blisters or road rash. New sneakers are the biggest culprit. "People buy what the magazine tells them to instead of using their head," he says. 8:43 a.m. Birkenfeld, on Highway 202 Yesterday's clouds have gone, and Van 1's second runner, Matt Henriksen, leaves in bright sunshine. "Performance varies with temperature, up to 10 minutes per race, I've found," John Ball says. A computer systems administrator, he's the team statistician. He not only keeps time, but he also actually wrote the spreadsheet software the team uses to predict finish times. Last year he was off by two minutes. After 27 hours. "I don't deal with the clipboard," Randy says when the subject comes up later. "I'm the big-picture guy." He's a bit like shock jock Howard Stern. Bawdy, authoritarian, fun-loving. People look for his pirate flag. The team evolves year after year, through family links and friends of friends. But Randy is the DNA upon which the Kult is based. 11:55 a.m. Leg 29, near the Nehalem River Bridge As Van 2 pounds out its third legs, the crowd is getting a bit loopy. People encourage total strangers. All runners finishing their third leg radiate glee. Sleepless pedestrians wander back and forth across the race path slowly. And there goes that boy in the dress again. Another Nike clone whizzes by. Goodness. Asked why they run this race, Kult Kevorkian members all hesitate. "I like it when I'm running in the Coast Range at night, and there's nothing but the stars and the sounds and smell of the forest," says Leah. "I do it 'cause it hurts," jokes Jared. Overall, he did 9:20s. "It forces you to get in shape," says John Ball. His brother Mike, who teaches math at Benson Tech, says, "The sense of achievement stays with you all year." 5:30 p.m. On the beach at Seaside Van 1, showered and in clean death's-head T-shirts, has been waiting, exhausted on the beach at Seaside for an hour. They spot Randy, his flag and his posse. Congratulations abound, and jokes are made about Van 1's slowness. This is no Nike team, but there's some pride at stake. The Hood to Coast Relay has multiple personalties. It's a showcase for Big Sportswear. A beauty pageant for the young and the hairless. A "Road Less Traveled" moment for folks who've resigned themselves to life in the slow lane. A fitness regime. The pursuit of happiness, against the clock. Randy has his own theory about why people do it. "It's like a cult! There's sleep deprivation, malnourishment and love bombing everyone telling you what a good job you've done. For one day of the year, you can join a cult." 5:40 p.m. Seaside Randy's wife, Kathy (course average 9:28), rounds the last bend with the baton, and all 12 jog painfully over the finish line, ready for their medals and their 15-second photo shoot. 6:30 p.m. Seaside It's all over, bar the limping. Tomorrow, the Kult will have breakfast in Cannon Beach, and some of them will see one another before next year's race. They bond, but not too much. Van 1 has a ritual: They go for pizza and sleep. Randy and Van 2 eat at the Pig 'N Pancake, then hit the party on the beach, mixing in with thousands of other elated runners as the sun goes down. The last thing visible is his pirate flag, disappearing into the crowd. Contact Joseph Gallivan at jgallivan@portlandtribune.com . Running the relay The Nationwide Insurance Hood to Coast Relay is the largest relay race in North America, stretching 197 miles from Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood to Seaside on the Pacific Ocean. A total of 12,000 runners in 1,000 teams of 12 enter the 36-leg race each year. Each participant runs three legs, totaling about 16 miles, although the terrain and the length of each leg varies. Because of the mixture of "elite" athletic teams and fun-runners, the average completion time is 26 to 27 hours. Teams divide into two groups of six, riding in vans ahead to the next exchange point. To be accepted, a team has to be able to run a mile in an average of 9 1/2 minutes. Teams wrongly estimating their completion time by plus or minus one hour can be penalized. Spinoff events such as the Portland to Coast Walk and the Portland to Coast High School Challenge run increase the number of competitors on the ground to 18,000. With 4,500 volunteers plus spectators, 95,000 people went to the finish line in 2002. This year's winner was a team of small-college athletes, the NCIC All Stars, with a time of 18 hours, 43 minutes and 33 seconds. That's 5:41's to you the average time for each mile they ran.

KULT KEVORKIAN MEMBERS 2003

Van 1

Mike Ball, 44

John Ball, 52, Mike's brother

Leah Henriksen, 24

Matt Henriksen, 25, Leah's husband

Jared Billings, 24, Mike Ball's former student

Kenneth Gibson, 26

Van 2

Randy Gibbs, 48, captain

Kathy Gibbs, 45, Randy's wife

Patty Payne, 33

Aaron Payne, 36, Patty's husband

Paul Pfeffer, 42

Ed Barker, 23

Kult Kevorkian finished in 581st place, at 27:53:24 and an average of 8:28

minutes per mile.